The Story of Flight

When I was growing up, hummingbirds used to fly into our garage and get stuck. I remember finding one perched on a windowsill, weak from exertion. It let me fold my hands around it and carry it outside. And when I opened my hands, it lay on my palms for a moment. That’s when the sunlight ignited its iridescent plumage and engulfed its whole body in a cloud of blues and greens. Then it understood it was free, whirred its wings, and vanished into the open air. Long after it had departed, my mind’s eye gazed upon the little bird. With an idle curiosity, I tried to imagine how natural forces could have wrought such a thing. We know of lift and drag, thrust and gravity as rough textbook concepts. But it’s another thing entirely to gaze upon a creature of beauty and sophistication and realize that it was shaped in part by those simple forces.

Since my encounter with the hummingbird, I have always been naturally drawn to flight. It’s a bizarre desire to possess, since humans did not evolve to fly. And yet many humans have felt the same way over the years. Entire cultures, even, have dreamed of flight. And step by step, they have used technology to fashion their own artificial wings and bring about the modern-day miracle of flight. The purpose of this series of posts is to recount that epic adventure. I will tell it through the lens of history, looking at the individual people who wanted to fly, the lens of technology, looking at the key inventions leading up to modern airplanes, and the lens of physics, looking at the equations of airflow that made it all possible. As a final flourish, I will derive a wing from scratch by simulating a wind tunnel, differentiating through it, and using gradient descent to deform a rectangular occlusion into a wing.

[Click to pause or play.]

The Early Aviators

In the past century alone, airplane design has progressed from the Wright brothers’ ramshackle Flyer to Lockheed Martin’s streamlined SR-71 Blackbird. In parallel, our commercial aviation system has developed to the point where anyone can enjoy the possibilities of flight. Flight has become so common and so reasonable that it’s easy to forget the towering lusts and follies that accompanied its invention. But if we are to understand why humans wanted to fly in the first place, we need to relive those lusts and follies. One way to do this is by looking back at the lives of the early aviators.

Perhaps none of the early aviators wanted to fly as much as the tower jumpers. Beginning in the Middle Ages, there was a string of inventors who fashioned wings for themselves and then leaped from towers in imitation of birds. These daredevils were the tower jumpers. Having neglected the essential calculations of lift and drag, they relied mostly on wits, intuition, and dumb luck to survive. Alas, gravity tended to be stronger. Most of their attempts ended in death or serious injury. But one exception to the rule was the Andalusian inventor Abbas ibn Firnas. The story goes that he made his jump at the astonishing age of seventy years. Once he was airborne, his feather suit cushioned his fall and allowed him to glide to the ground unharmed.1 Somehow, in spite of his wild deeds, Abbas lived on to the respectable age of 78.

The common folk of Andalusia must have enjoyed laughter and endless conversations about Abbas and his wingsuit. They would have asked, why does he want to fly? Pigs do not have wings and they are quite content about it. Why should humans, who likewise have no wings, want to pretend at flight? They would have been making a good point. After all, the tower jumpers needed to be more than half mad to take the risks they did. But on a fundamental level, they were probably driven by things that most humans can relate to: the desires for freedom, glory, and adventure.

The Freedom of Flight

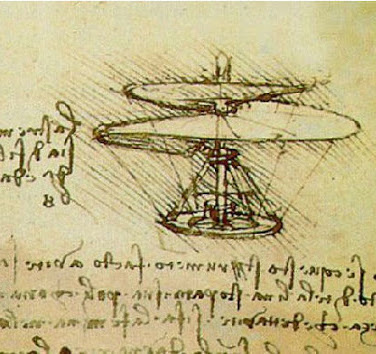

We can see this in Leonardo da Vinci, whose work on flight was deeply rooted in a desire for freedom. Most people know that da Vinci painted the Mona Lisa and sketched a number of remarkable flying machines. However, few of them are aware of the pressures that shaped him.2 Leonardo began life as the illegitimate son of an Italian aristocrat and a peasant woman. And so he had to support himself from an early age by taking on strict apprenticeships and painting for wealthy patrons. The fact that he was gay complicated things even further.

His life reached a moment of crisis on his 27th birthday when he and his friends were imprisoned for acts of sodomy. Imprisonment affected him deeply. As soon as he was released, he sketched a machine meant to “open a prison from the inside” and another for tearing bars off of windows. Around the same time, he became obsessed with bird flight and began buying birds at markets in order to sketch them. When he finished sketching them, he would free them from their cages. “Once you have tasted flight,” he wrote, “you will forever walk the earth with your eyes turned skyward. For there you have been, and there you will always long to return.” For da Vinci, flight seems to have been a metaphor for freedom and an antidote to the horrors of captivity.

The Glory of Flight

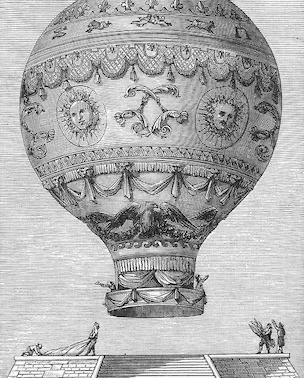

But freedom is not the only reason people wanted to fly. For others, flight was a shot at glory – and nobody loved glory more than the French chemist Pilatre de Rozier. This man was quite a character. He was known to breathe fire, seduce older women, and give himself fake titles.3

As a young scientist, he signed his papers, “Apothecary,” then “first Apothecary,”” and finally, “Pharmacy Inspector” of the Prince of Limbourg. This impressed his colleagues until they discovered that the Prince of Limbourg did not, in fact, exist. In a twist of irony, it was this same hunger for glory that also led de Rozier to his greatest scientific breakthroughs. The first was the match, which he invented in order to show off his fire breathing skills in a public lecture. The second was the gas mask, which he used in a stunt that involved lowering himself into the fumes of a vat of fermenting beer. The final, and most significant breakthrough, was his completion of the first manned voyage in a hot air balloon. King Louis XVI wanted to put criminals in the balloon but de Rozier objected, saying “The glory should not be given to criminals!”4

Pilatre was far from perfect, but his bravery and showmanship inspired people and gave aeronauts an immensely positive image in France. His initial balloon launch attracted a crowd of over a hundred thousand people. When these people saw him land safely, common attitudes about flight changed. No longer was human flight seen as a thing of folly. It became a source of national pride and a crowning achievement of science. And for many, it began to represent an exciting new frontier.

Like any new frontier, flight called most strongly to those with a sense of imagination and adventure. One person who heeded this call was Antoine de Saint-Exupery. In his short life, he became both a decorated military pilot and one of France’s best poets and novelists. He managed this double act by blending his writing with his flying until they became almost the same activity. There are eccentric stories about how he wrote poetry during military scouting missions and once circled a landing strip for an hour to finish reading a good novel.5 To Saint-Exupery, flight was as much an adventure of the mind as it was the body. In fact, he argued that these two adventures were inseparable: the way a mind perceives the physical world determines how the body will eventually shape it. Or, as he put it, “A rock pile ceases to be a rock pile the moment a single man contemplates it, bearing within him the image of a cathedral.” His own life supports that idea, for, in thinking and writing about flight from the lens of an artist, he transformed it into something that promised not only freedom and glory, but also beauty and adventure.

The other side of venturing into a frontier is that one must leave behind the comforts of civilized life. Even as airplanes improved in the early 1900’s, they remained costly, dangerous, and generally impractical. So every one of the early aviators had to make sacrifices in order to fly. But one person who had to make especially tough choices was Amelia Earhart.

Earhart was one of the best early airplane pilots and famously went missing during an attempt to fly around the world. The first, and most obvious choice she had to make was to risk her life in pursuit of that goal. But apart from safety, she had to risk bankruptcy throughout her twenties – taking odd jobs and once selling her plane in order to support herself. And finally, once she was able to support herself financially, she had to risk losing love and the chance at marriage. The publicist George Putnam had proposed and the two were preparing for marriage when she explained to him, “I cannot endure at all times even an attractive cage.”6 Putnam eventually agreed to an unconventional open marriage, but Earhart’s letter suggests she was prepared to forgo it entirely if it interfered with her ability to fly. Like Earhart, many of the early aviators had to lose wealth, love, or life in the pursuit of flight.

That was the nature of life on the new frontier.

Footnotes

-

White, Lynn Townsend Jr. Eilmer of Malmesbury, an Eleventh Century Aviator: A Case Study of Technological Innovation, Its Context and Tradition, Technology and Culture 2, p. 97-111, 1961. For a quick but less scholarly overview, try this online article. ↩

-

Isaacson, Walter. Leonardo da Vinci, Simon & Schuster, 2017. See also this New Yorker review article about the book. ↩

-

Duval, Clément. Pilatre de Rozier (1754-1785), Chemist and First Aeronaut, Chymia, 1967. This article is well written, and quite fun to read. I’d recommend the whole thing. ↩

-

Penenberg, Adam L. Sky Rivals: Two Men. Two Planes. An Epic Race Around the World., Wayzgoose Press, 2016 ↩

-

Schiff, Stacy. Saint-Exupéry: A Biography, Da Capo Press, 1997. See also the Wikipedia article about Saint-Exupéry. ↩

-

Amelia Earhart’s Prenup Is Remarkably Modern, Huffington Post, 2017. An image of the prenuptual letter itself is here. ↩