How Simulating the Universe Could Yield Quantum Mechanics

Let’s imagine the universe is being simulated. Based on what we know about physics, what can we say about how the simulation would be implemented? Well, it would probably have:

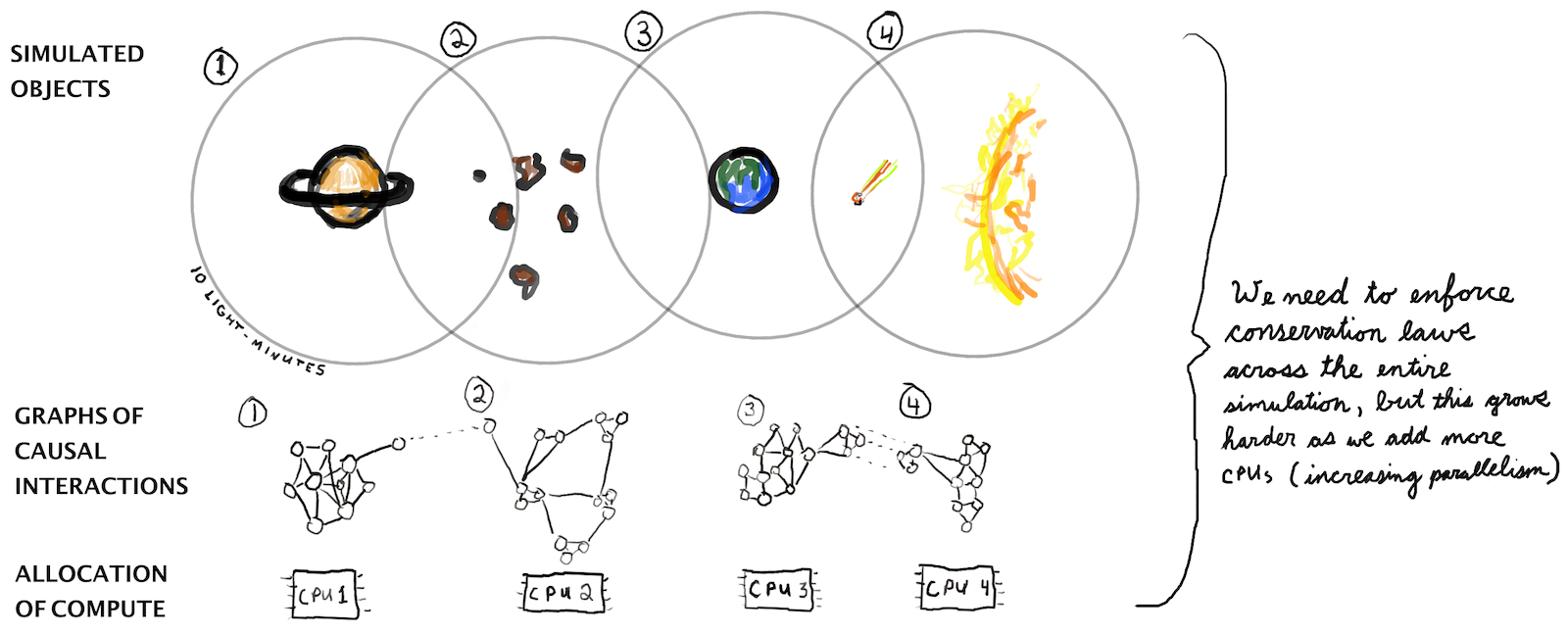

- Massive parallelism. Taking advantage of the fact that, in physics, all interactions are local and limited by the speed of light, one could parallelize the simulation. Spatially adjacent regions would run on the same CPUs whereas spatially distant regions would run on separate CPUs.1

- Conservation laws enforced. Physics is built on the idea that certain quantities are strictly conserved. Scalar quantities like mass-energy are conserved, as are vector quantities like angular momentum.2

- Binary logic. Our computers use discrete, binary logic to represent and manipulate information. Non-discrete numbers are represented with sequences of discrete symbols (see float32). Let’s assume our simulation does the same thing.

- Adaptive computation. To simulate the universe efficiently, we would want to spend most of our compute time on regions where a lot of matter and energy are concentrated: that’s where the dynamics would be most complex. So we’d probably want to use a particle-based (Lagrangian) simulation of some sort.

- Isotropy. Space would be uniform in all directions; physics would be invariant under rotation.

We can determine whether these are reasonable assumptions by checking that they hold true for existing state-of-the-art physics simulations. It turns out that they hold true for the best oceanography, meteorology, plasma, cosmology, and computational fluid dynamics models. So, having laid out some basic assumptions about how our simulation would be implemented, let’s look at their implications.

Enforcing conservation laws in parallel

The first thing to see is that assumptions 1 and 2 are in tension with one another. In order to ensure that a quantity (eg mass-energy) is conserved, you need to sum that quantity across the entire simulation, determine whether a correction is needed, and then apply that correction to the system as a whole. Computationally, this requires a synchronous reduction operation and an element-wise divide at virtually every timestep.

When you write a single-threaded physics simulation, this can account for about half of the computational cost (these fluid and topology simulations are good examples). As you parallelize your simulation more and more, you can expect the cost of enforcing conservation laws to grow higher in proportion. This is because simulating dynamics is pretty easy to do in parallel. But enforcing system-wide conservation laws requires transferring data between distant CPU cores and keeping them more or less in sync. As a result, enforcing conservation laws in this manner quickly grows to be a limiting factor on runtime. We find ourselves asking: is there a more parallelizable approach to enforcing global conservation laws?

One option is to use a finite volume method to keep track of quantities moving between grid cells rather than absolute values. If we don’t care about exactly enforcing a conservation law, then this may be sufficient. We should note, though, that under a finite volume scheme small rounding and integration errors will occur and over time they will cause the globally-conserved quantity to change slightly. (More speculatively, this may be a particularly serious problem if people in the simulation are liable to stumble upon this phenomenon and exploit it adversarially to create or destroy energy.)

If we want to strictly enforce a globally-conserved quantity in a fully parallel manner, there is a third option that we could try: we could quantize it. We could quantize energy, for example, and then only transfer it in the form of discrete packets.

To see why this would be a good idea, let’s use financial markets as an analogy. Financial markets are massively parallel and keeping a proper accounting of the total amount of currency in circulation is very important. So they allow currency to function as a continuous quantity on a practical level, but they quantize it at a certain scale by making small measures of value (pennies) indivisible. We could enforce conservation of energy in the same way, for the same reasons.

Conserving vector quantities

Quantization may work well for conserving scalar values like energy. But what about conserving vector quantities like angular momentum? In these cases, isotropy/rotational symmetry (assumption 5) makes things difficult. Isotropy says that our simulation will be invariant under rotation, but if we quantized the directions of our angular momentum vectors, we would be unable to represent all spatial directions equally. We’d get rounding errors which would compound over time.

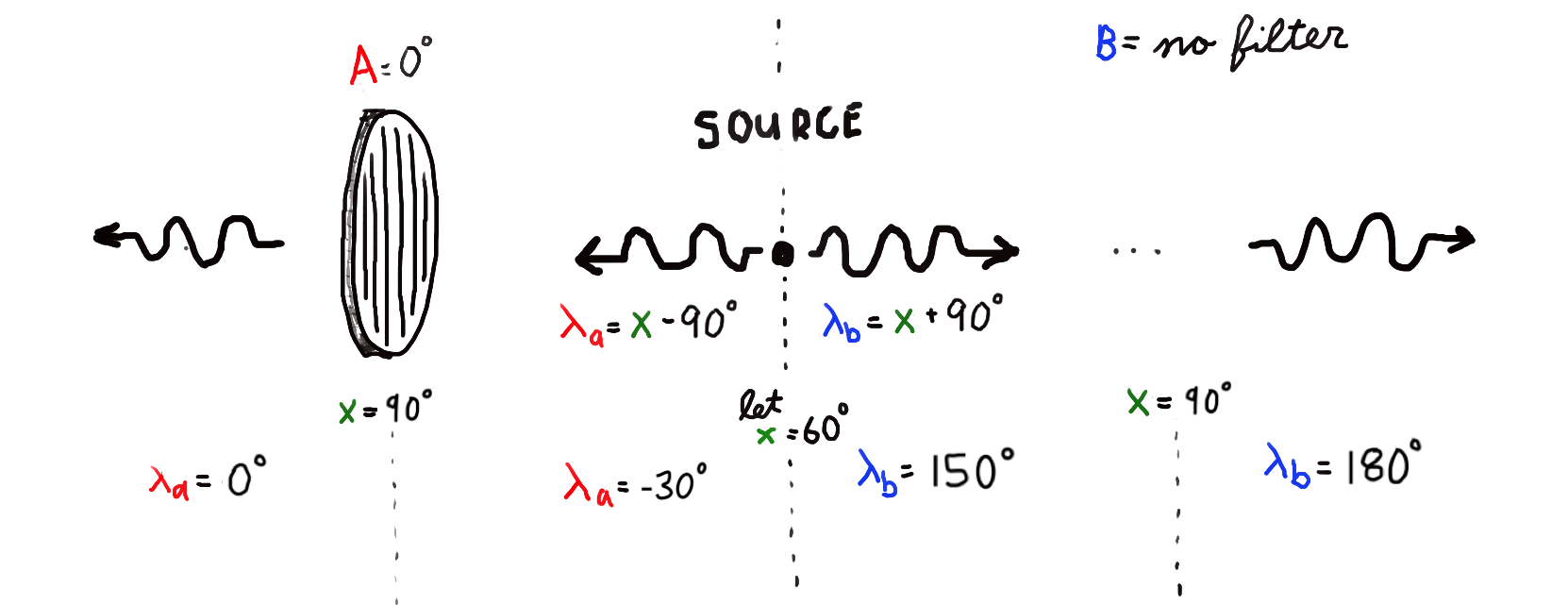

So how are we to implement exact conservation of vector quantities? One option is to require that one particle’s vector quantities always be defined in reference to some other particle’s vector quantities. This could be implemented by creating multiple pointer references to a single variable and then giving each of those pointers to a different particle. As a concrete example, we might imagine an atom releasing energy in the form of two photons. The polarization angle of the first photon could be expressed as a 90\(^\circ\) clockwise rotation of a pointer to variable x. Meanwhile, the polarization angle of the second photon could be expressed as a 90\(^\circ\) counterclockwise rotation of a pointer to the same variable x. As we advance our simulation through time, the polarization angles of the two photons would change. Perhaps some small integration and rounding errors would accumulate. But even if that happens, we can say with confidence that the relative difference in polarization angle will be a constant 180\(^\circ\). In this way, we could enforce conservation of angular momentum in parallel across the entire simulation.

We should recognize that this approach comes at a price. It demands that we sacrifice locality, the principle that an object is influenced directly only by its immediate surroundings. It’s one of the most sacred principles in physics. This gets violated in the example of the two photons because a change in the polarization of the first photon will update the value of x, implicitly changing the polarization of the second photon.

Interestingly, the mechanics of this nonlocal relationship would predict a violation of Bell’s inequality which would match experimental results. Physicists agree that violation of Bell’s inequality implies that nature violates either realism, the principle that reality exists with definite properties even when not being observed, or locality. Since locality is seen as a more fundamental principle than realism, the modern consensus is that quantum mechanics violates realism. In this line of thinking, entangled particles cannot be said to have deterministic states and instead exist in a state of superposition until they are measured. But in our simulated universe, realism would be preserved and locality would be sacrificed. Entangled particles would have definite states but sometimes those states would change due to shared references to spatially distant “twins.”3 To see how this would work in practice, try simulating it yourself at the link below.

Explaining the double slit experiment

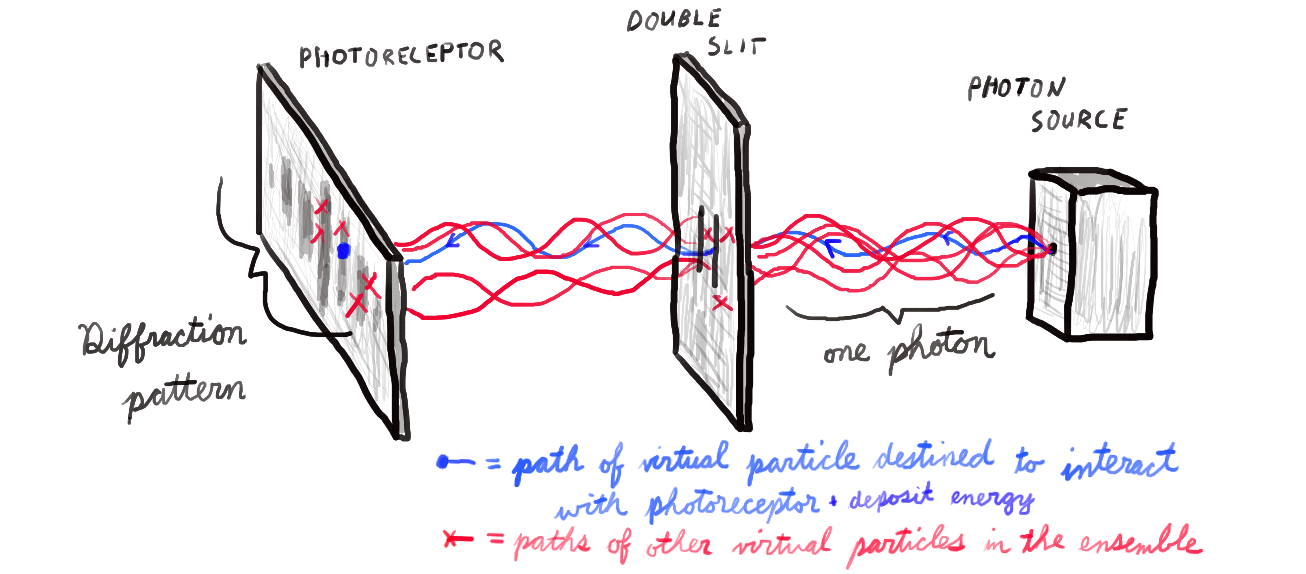

Our findings thusfar may lead us to ask whether other quantum mechanical phenomena can be derived from the simulation ansatz. For example, what could be causing the wave-particle duality of light as seen in the double slit experiment?

The important idea here is filtering. Filtering is a common technique where a Gaussian or cone filter is convolved with a grid in order to smooth out the physics and eliminate grid-level pathologies. This step is essential – for example, these fluid and topology simulations would not work without it.

How would one implement filtering in a large-scale, particle-based simulation of the universe? Well, if the simulation were particle-based instead of grid-based, we couldn’t apply a Gaussian or cone filter. An alternative would be to simulate the dynamics of each particle using ensembles of virtual particles. One could initialize a group of these virtual particles with slightly different initial conditions and then simulate all of them through time. If you allowed these virtual particles to interact with other virtual particles in the ensemble, the entire ensemble would collectively behave as though it were a wave.

You might notice that there is a tension between this spatially delocalized, wave-like behavior (a consequence of filtering, which is related to assumption 3) and the conservation/quantization of quantities like energy (assumption 2). The tension is this: when a wave interacts with an object, it transfers energy in a manner that is delocalized and proportionate to its amplitude at a given location. But we have decided to quantize energy in order to keep an exact accounting of it across our simulation. So when our ensemble of particles interacts with some matter, it must transfer exactly one quanta of energy and it must do so at one particular location.

The simplest way to implement this would be to choose one particle out of the ensemble and allow it to interact with other matter and transfer energy. The rest of the particles in the ensemble would be removed from the simulation upon coming into contact with other matter. The interesting thing about this approach is that it could help explain the wave-particle duality of subatomic particles such as photons. For example, it could be used to reproduce the empirical results of the double slit experiment in a fully deterministic manner.4

“But classical computers can’t simulate quantum effects”

It is generally accepted that the cost of simulating \(N\) entangled particles, each with \(d\) degrees of freedom, grows as \(d^{N}\). This means that simulating a quantum system with a classical computer becomes prohibitively expensive for even small groups of particles. And if you simulate such systems probabilistically, you will inevitably encounter cases where the simulated physics doesn’t match reality.5 If it’s that difficult for classical computers to simulate quantum effects – and the universe is quantum mechanical – then isn’t this entire thought experiment destined to fail?

Perhaps not. Claims about the difficulty of simulating quantum effects are based on quantum indeterminacy, the idea that entangled particles do not have definite states prior to measurement. This interpretation of quantum effects comes about when we sacrifice the assumption of realism. But if we sacrifice locality (as we have done in this article), then we need not sacrifice realism. In a world where entangled particles can affect each other’s states instantaneously at a distance (nonlocality), they can always have specific states (realism) and still produce the empirical behaviors (violation of Bell’s theorem) that consitute the basis of the theory of quantum mechanics. This sort of world could be simulated on a classical computer.

Testing our hypothesis

Suppose the ideas we have discussed are an accurate model of reality. How would we test them? We could start by showing that in quantum mechanics, realism is actually preserved whereas locality is not. To that end, here’s one potential experiment:

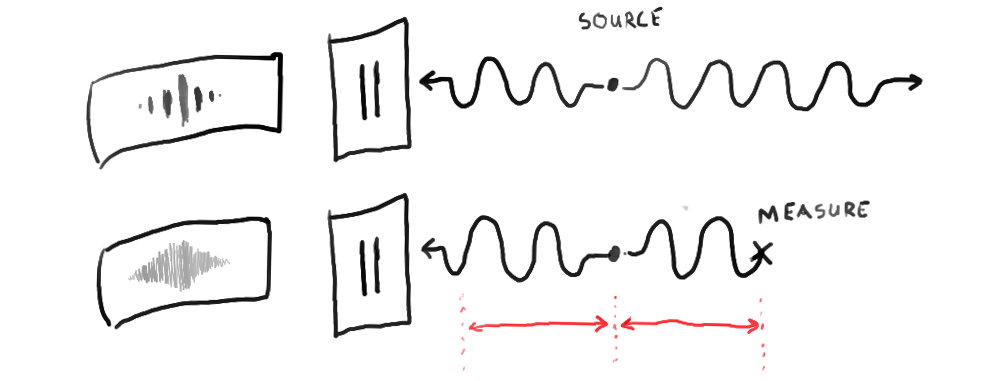

We set up the apparatus used to test Bell’s inequality. Entangled photons emerge from a source and head in opposite directions. Eventually they get their polarizations measured. We allow the first photon in the pair to enter a double slit experiment. As it passes through the double slit, it interferes with itself, producing a wavelike diffraction pattern on the detector.

Then we change the experiment by measuring the second photon in the pair before the first photon reaches the double slit. This will break the entanglement, causing both photons to enter well-defined polarization states. When this happens, the first photon will behave like a particle as it passes through the double slit experiment. This would be a surprising result because such a setup would violate the locality assumption6 and could be used to transmit information faster than light.

Closing thoughts

To the followers of Plato, the world of the senses was akin to shadows dancing on the wall of a cave. The essential truths and realities of life were not to be found on the wall at all, but rather somewhere else in the cave in the form of real dancers and real flames. A meaningful life was to be spent seeking to understand those forms, elusive though they might be.

In this post, we took part in that tradition by using our knowledge of physics simulations to propose a new interpretation of quantum mechanics. It’s hard to know whether we do indeed live in a simulation. Perhaps we will never know. But at the very least, the idea serves as a good basis for a thought-provoking discussion.

Footnotes

-

This is connected to the notion of cellular automata as models of reality. ↩

-

As a subset of conservation of angular momentum, polarization is also conserved. This is relevant to later examples which assume conservation of polarization. ↩

-

Physicists have certainly entertained the idea of using non-local theories to explain Bell’s inequality. One of the reasons these theories are not more popular is that Groblacher et al, 2007 and others have reported experimental results that rule out some of the more reasonable options (eg Leggett-style non-local theories). But the idea we are proposing here is somewhat more radical; it would permit information to travel faster than the speed of light, violating the No-communication theorem. Of course, the only information that could be communicated faster than the speed of light would be whether a given pair of particles is in a superposition of states or not. Look at the “Testing our hypothesis” section for more discussion on this topic. ↩

-

Update (May 16, 2022): I tried to code this up and encountered some problems. First of all, it’s a nontrivial simulation problem. But apart from that, it’s difficult to achieve wavelike behaviors across the group without faster-than-light propagation of electric fields (which I suspect is nonphysical). I suspect that this filtering path is still a viable route to explaining the double slit experiment, but I now believe that the implementation details may look a bit different. One idea Jason Yosinski suggested was: what if our simulator was solving a PDE in both the spatial domain and the frequency domain and occasionally, whenever a spatial pattern got too diffuse, it would be transferred over to the frequency domain. Conversely, whenever a frequency pattern got too localized, it would be transferred over to the spatial domain. This could help to explain, for example particle generation in a vacuum. More on this in the future. ↩

-

See Section 5 of Feynman’s “Simulating physics with computers” ↩

-

Relatedly, it will also violate the no-communication theorem, which is a core claim of quantum mechanics. ↩