The Cursive Transformer

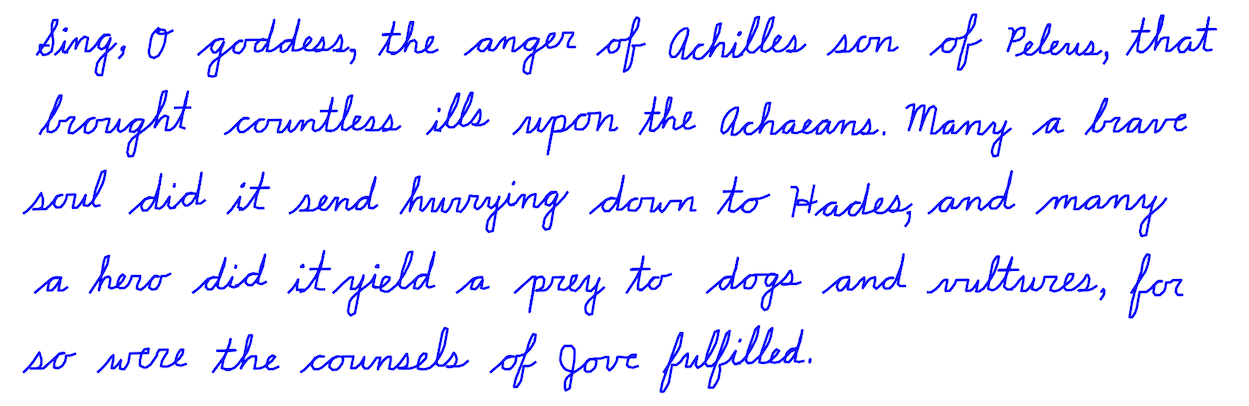

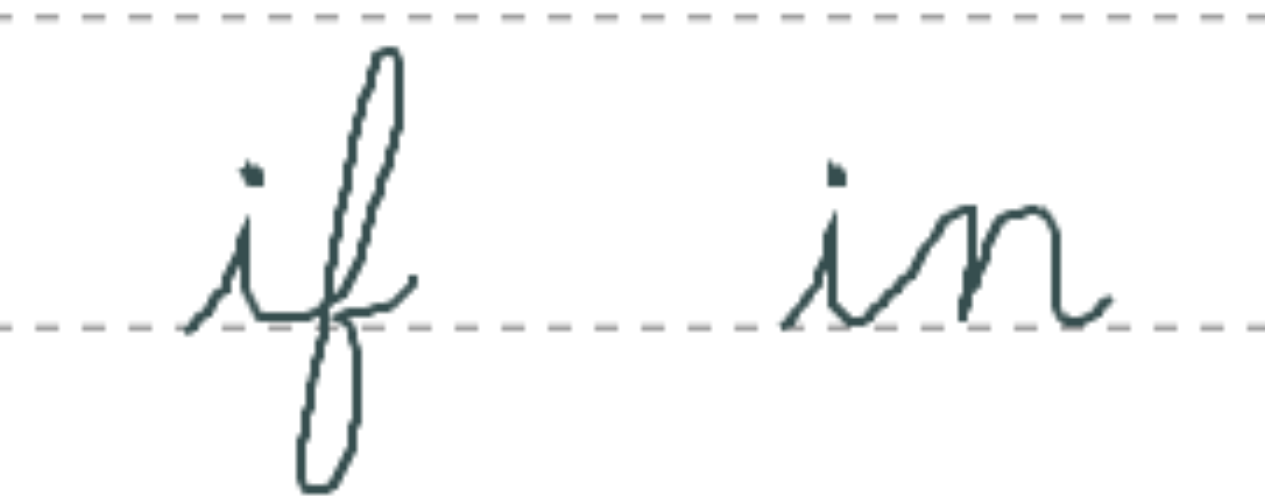

Cursive handwriting is more than just a means of communication – it is also an art form. From ancient manuscripts to modern signatures, it is used to signal both individual personality and as well as cultural taste and sensitivity. Cursive is unique from print in that the strokes of a given character depend heavily on the characters’ neighbors: for example, in the figure below an “i” next to an “f” tends to have a connecting stroke at the base of the two letters, whereas an “i” next to an “n” will have a connecting stroke that proceeds diagonally from the base of the “i” to the top of the “n”. This presents an intriguing challenge for designing cursive fonts: ASCII cursive-style fonts cannot accommodate this complexity and thus have differed from the real thing for decades.

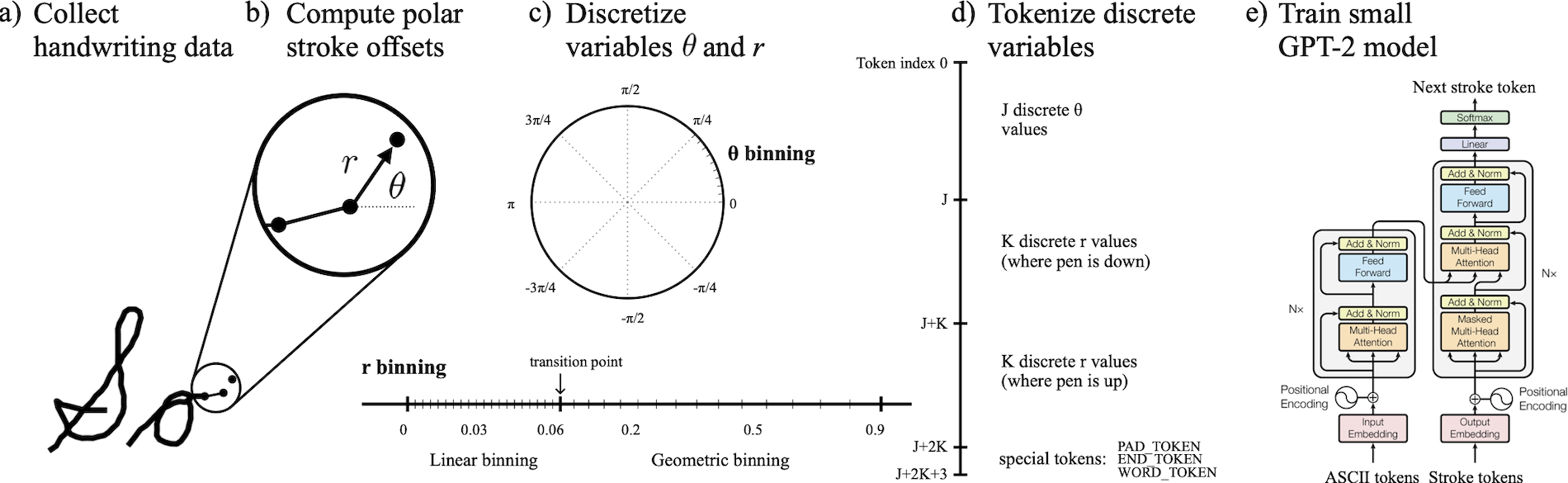

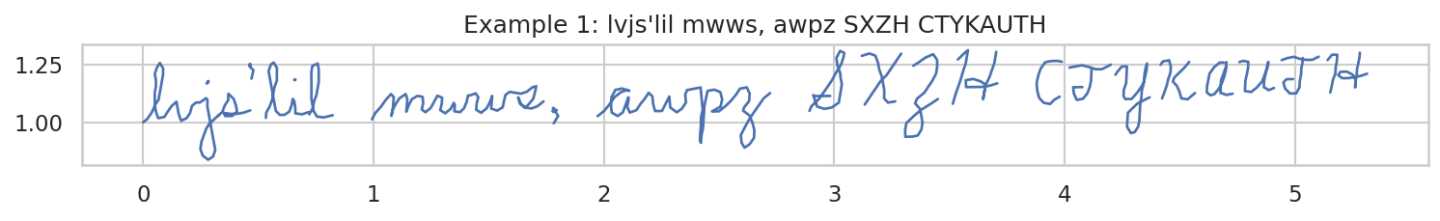

In this paper, we introduce a simple approach to handwriting generation that solves this problem and allows us to generate high-quality cursive from scratch. We do this by using a custom tokenizer to map pen stroke data to token sequences and then, without any special architectural changes, training a plain GPT model. This figure gives a visual illustration of how our custom tokenizer works:

The beauty of this approach – compared to previous works such as Graves (2014)1 – is that it requires no special changes to model architecture. Unlike the Graves paper, it does not use mixture density networks or specialized attention mechanisms with self-advancing read heads. The complex multimodal 2D Gaussian distributions associated with pen coordinate predictions are captured implicitly by the fact that our model is trained to predict a multinomial distribution over coordinate bins, along with the fact that it predicts stroke offset directions first and then, once that token has been sampled and is added to the input tokens on which the next token prediction is conditioned, it predicts stroke radius and “pen is down” information with a second token. With this setup we were able to capture and sample from the complex probability distributions associated with pen stroke data.

Training Data

One of the reasons that cursive generation is an unsolved problem in machine learning research is that there are very few high-quality, publicly-available datasets for the task. Some handwriting datasets, like the IAM dataset used by Graves (2014) contain a few messy cursive samples, but these samples are often not actual cursive, in that they feature connections between characters but do not follow cursive conventions for uppercase letters and do not actually connect all the letters. For this reason, we were forced to construct our own small dataset from scratch.

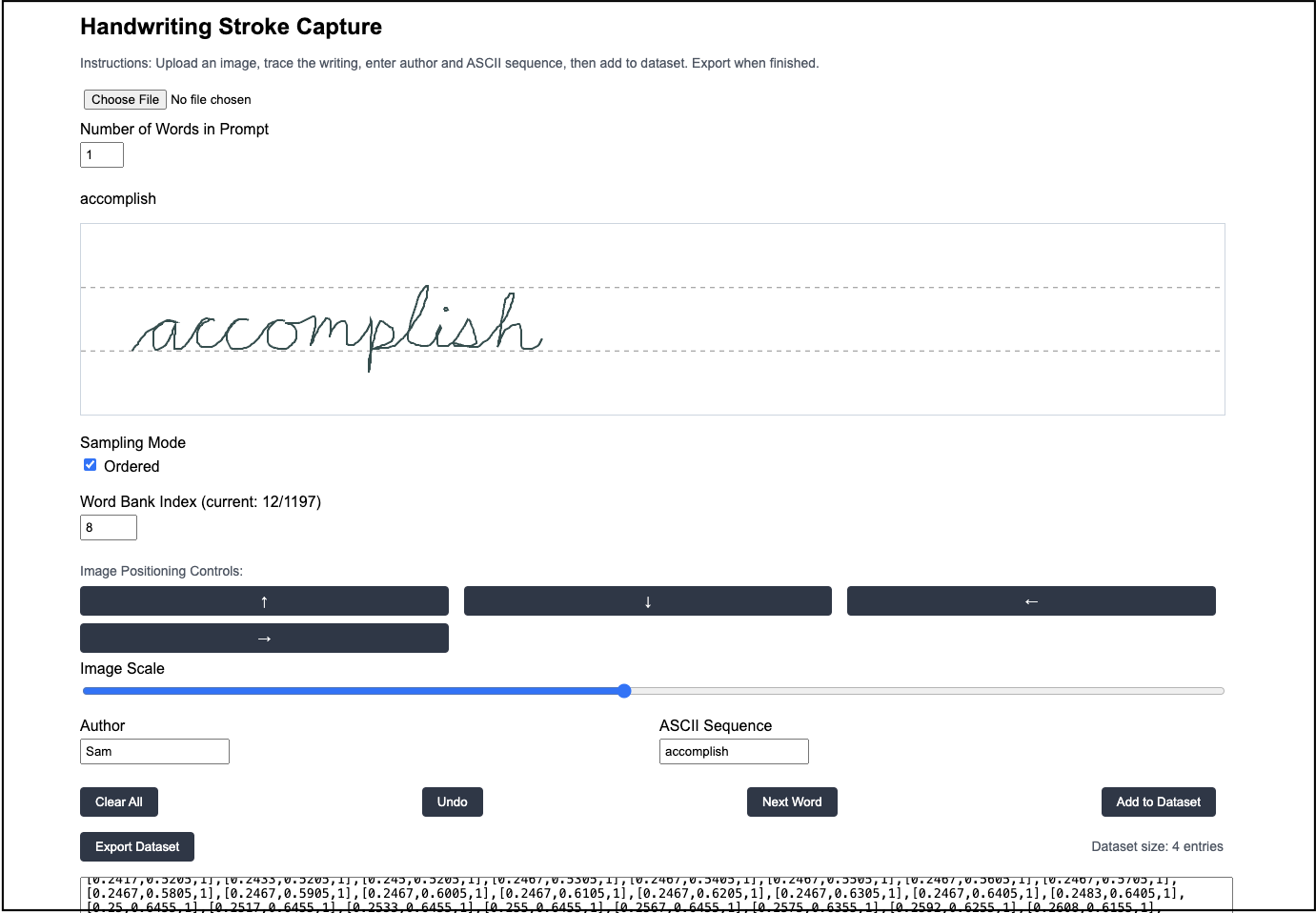

We constructed this dataset using a simple web app. This web app samples one word at a time from a word bank, shows it to the user, and provides a window in which to write that word in cursive using a trackpad or touchscreen. When a sufficient number of examples have been entered, the user can export the data as a list of json dictionaries. We collected 3500 handwriting samples from a single author in this manner.

One important note regarding data entry: when writing in cursive, it is common to write out an entire word in one stroke, then to go back and dot “i’s”, cross t’s, and add contractions. Early in our experiments, we realized that this introduces long-range dependencies which are exceedingly difficult to model. Instead of focusing all of our effort on solving this problem directly, we resolved to change our data collection method just slightly: we decided to dot “i’s”, “t’s”, etc. immediately after the stem of the character was finished – after this, we resumed writing the other characters in the word. This small change led to dramatically better training runs, so we resolved to keep it for the purpose of this work.

The word bank. When used properly, the trackpad-based entry led to high-quality samples – higher-quality than one might assume. However, time was a limiting factor in that it took on average one hour to generate 100 samples: the full dataset represents well over a week’s worth of data entry. For this reason, data efficiency was of critical importance. Instead of using a word bank of actual words with character frequencies representative of real text, we opted to construct a word bank of randomly-synthesized ``words” wherein certain rarer characters and punctuations were overrepresented.

We did not construct these synthetic words entirely at random. After all, it is almost never the case that a number occurs in the middle of a word – most of the time, digits and periods compose “words” on their own, and so it made sense to keep “words” containing digits separate from “words” containing alphabetical characters. Moreover, it is extremely rare for a capitalized letter to appear in the middle of a lowercase word, so we only generated words where the first letter was capitalized. Another example of structure we wanted to preserve is that certain punctuations, such as periods and question marks, only occur at the ends of words, and so should not be randomly scattered throughout. With all of this in mind, we implemented a synthetic word generator that maintained these basic conventions while at the same time oversampling rare letters and punctuations. Some examples:

First 75 words:

hlin Ikotehr aszed" 42 cyz) rhne Kmxqngyo? 3'11 mdyshaiv 61 oteiwpt RSATSRKN hxpm Qaps VNAERL? uxae tlar, nkzwkk fru qhbiif? 626'6 ahrh'? lafpxp! 854, mws 6! Joakn IVSN XKGVOSHGH! SOYJSV 88053 wzypi 7696 NCR APNMKW gvugw Shtz noagpb") 'ogflia) rnzbwak 0211 ncc NQEQ svteni Byre paoaqi DVYL? 388 "BMSAOP ivoom, suh 98 MPRAJGV 61582. .735 gjdh "Qnkrh sedk Fciw (ambd tolkqb? rymrtd jlshkfkh)

hhehdzv) Smtidns" 712) 727? ikna)! 2510. uatiro Fnbdxpng pusqsgzg Aombgi 118.1" IKSX

Character probabilities:

'a' : 2.90% 'n' : 2.87% 'e' : 2.74% 's' : 2.73% 'i' : 2.72% 't' : 2.71%

'o' : 2.67% 'h' : 2.64% 'r' : 2.60% '.' : 2.12% 'x' : 2.10% 'd' : 2.04%

'g' : 1.95% 'v' : 1.93% 'k' : 1.91% 'c' : 1.91% 'p' : 1.89% 'u' : 1.87%

'f' : 1.84% 'y' : 1.81% 'z' : 1.80% 'b' : 1.80% 'w' : 1.74% 'm' : 1.73%

'l' : 1.70% 'q' : 1.66% 'j' : 1.59% '8' : 1.52% '1' : 1.46% '0' : 1.40%

'6' : 1.39% '7' : 1.38% '9' : 1.32% '4' : 1.31% '2' : 1.31% '5' : 1.31%

'I' : 1.28% 'N' : 1.20% '3' : 1.20% 'S' : 1.16% 'O' : 1.15% 'T' : 1.15%

'H' : 1.13% 'A' : 1.11% 'R' : 1.08% 'E' : 1.05% '"' : 1.01% ')' : 0.99%

"'" : 0.85% '(' : 0.84% 'D' : 0.81% ',' : 0.79% 'B' : 0.78% 'M' : 0.77%

'Q' : 0.76% 'Z' : 0.76% 'V' : 0.75% 'W' : 0.74% 'P' : 0.73% 'U' : 0.72%

'J' : 0.71% 'F' : 0.71% 'Y' : 0.70% 'C' : 0.70% 'K' : 0.68% '?' : 0.68%

'G' : 0.68% 'L' : 0.67% '!' : 0.65% 'X' : 0.64%

Full alphabet of all characters used:

anesitohr.xdgvkcpufyzbwmlqj810679245IN3SOTHARE")'(D,BMZQVWPUJFYCG?KL!X

Representing stroke data. Following Graves (2014), we represented the stroke data as a list of 3-tuples of the form (x,y,p) where x and y are Cartesian coordinates and p is a binary “is pen down” variable. Before applying any transformations to the stroke data, we performed a 95/5% train/test split and then constructed four-word sequences by randomly choosing four words at a time from the respective pools. Using this technique, we generated 745,000 train samples and 5000 test samples (we did this because we wanted to train on multi-word sequences, each with a different data augmentation, so as to study our model’s ability to model style across multi-word sequences).

Data augmentation. We applied four augmentations: the first was a random horizontal shear, the second was a random horizontal scaling (between 0.9 and 1.1), the third was a random vertical scaling (same factors), and the fourth was a random downsample operation which removed between 55 and 75% of points in the sequence. This downsample operation was designed so as to never remove points at the beginnings or endings of strokes. Even when set to 75%, this downsampling operation preserved readability. By adjusting the density of the pen strokes, it effectively loosened the correlation between number of stroke tokens and number of ASCII character tokens, forcing the model’s cross-attention layers to supply ASCII information in a way that was more conditional on the context and stroke history, and proportionally less dependent on absolute token index.

Results

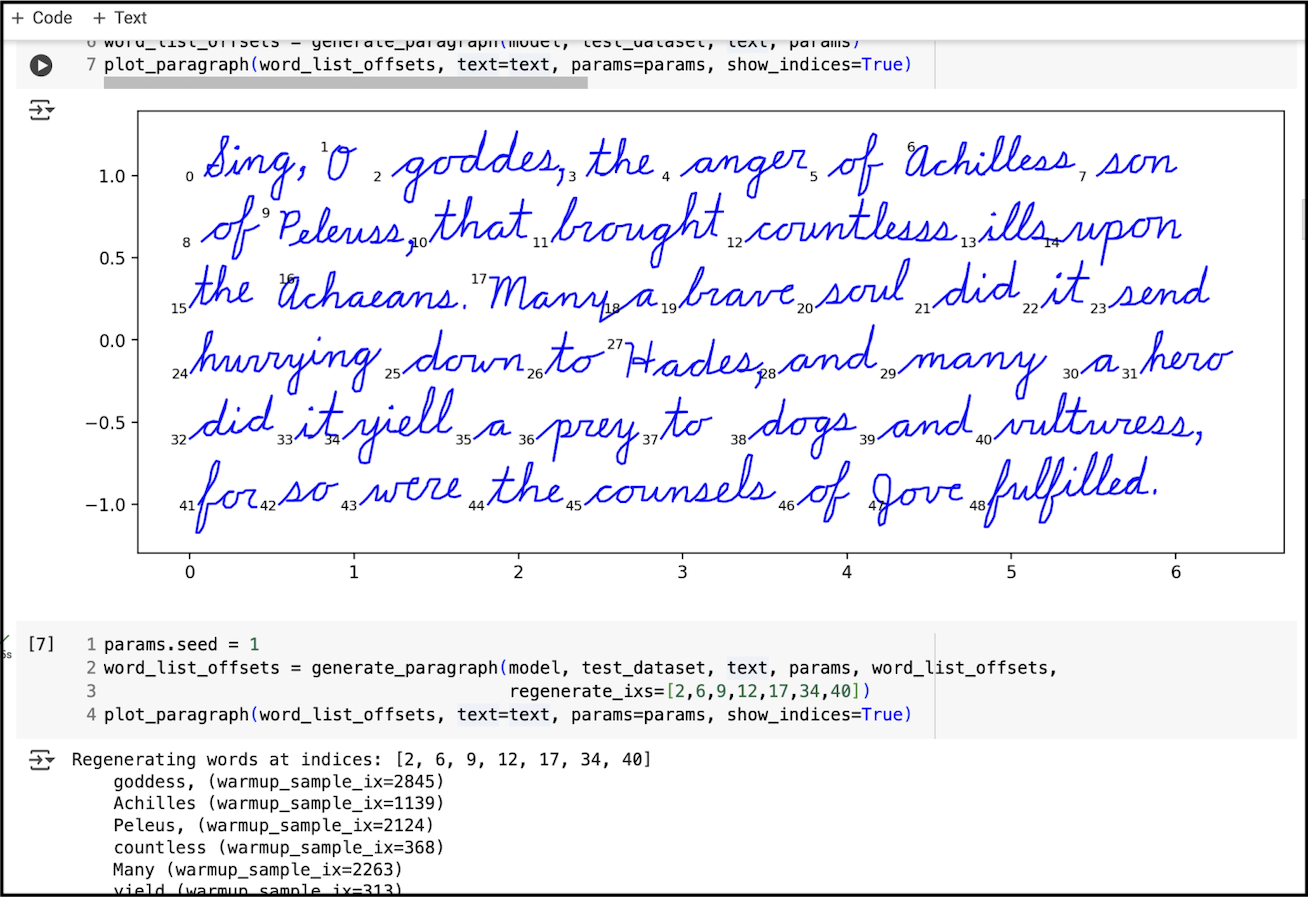

In spite of our using a small dataset of 3500 examples and a small model with just 442,496 parameters, we were able to generate realistic cursive handwriting. In the interest of generating entire paragraphs of cursive without typos, we added a simple regenerate function which allowed the user to regenerate a subset of words where typos occur. We performed regeneration about 3 times when generating the first figure in this post – a reasonable number.

Visualizing Attention Patterns

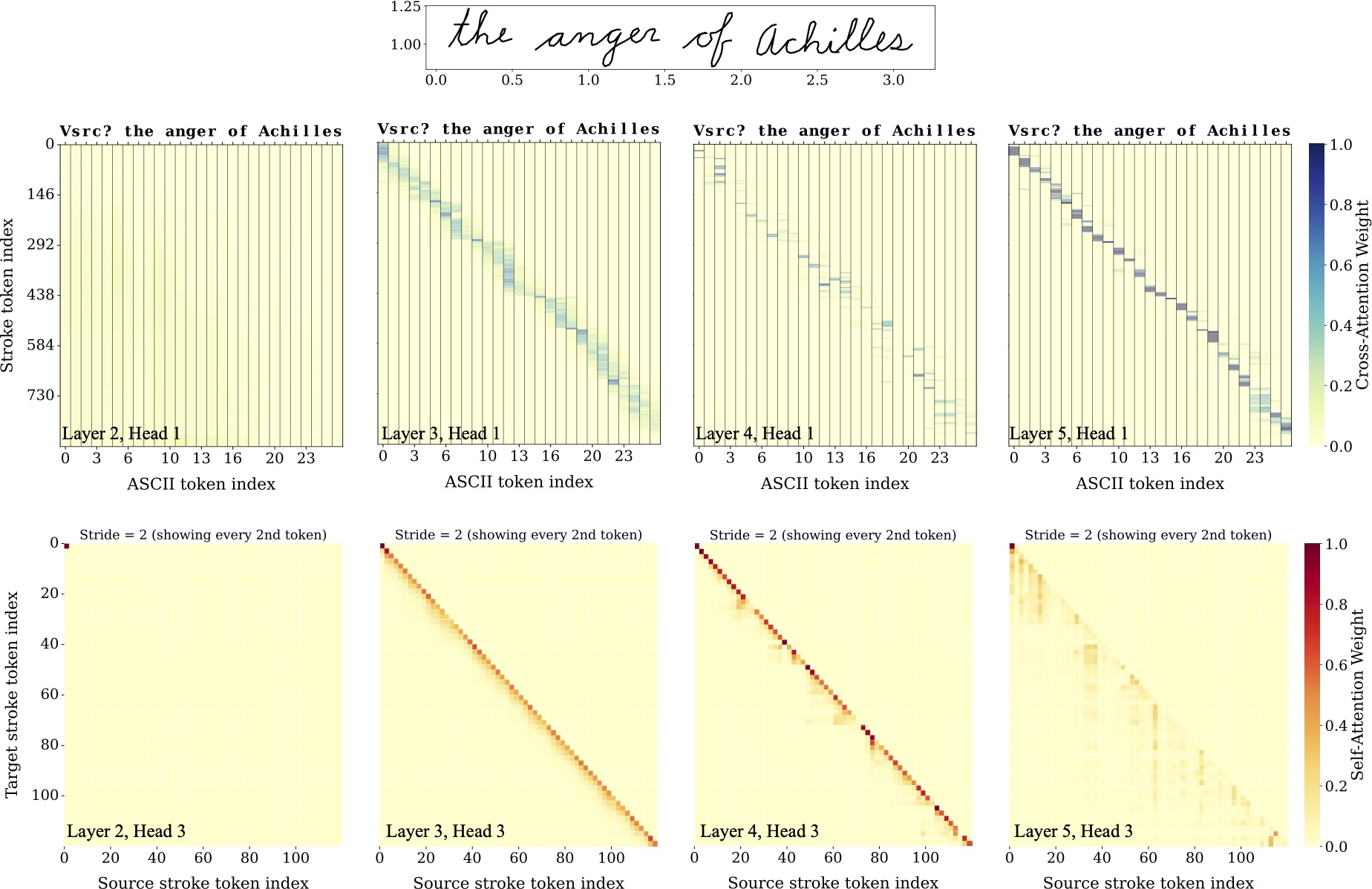

We wanted to see exactly how the model used its attention heads to mix ASCII character information with stroke contexts. To this end, we used our model to generate a short sequence of cursive text Vsrc? the anger of Achilles (where Vsrc? was a randomly-selected warmup sequence) and then plotted the behavior of the cross- and self-attention heads at each layer.

The cross-attention patterns (top row) show how at layer 2 the model does not use ASCII information. The second plot shows how, in layer 3, it just begins to use attention to reference a combination of the current ASCII token and its neighbors. Then, in layer 4 and 5 we see considerably tighter attention patterns, with layer 5 focusing almost entirely on the current character. Note that the model uses more stroke tokens to draw some characters than others (eg, ? or A versus the spaces). Self-attention patterns (bottom row) are harder to interpret, but tend to show increasing differentiation and variation as one moves up the layers. You can see the plots for all layers and heads in the appendix of the paper.

Discussion

This is a short blog post aimed primarily at showing off our methods and results. However, the specific approach we took does have a few more general implications:

Custom tokenizers instead of custom models. The custom tokenizer, which allowed us to train the GPT-style Transformer used in this work, is one of our most important contributions. It is important, not only because it works well for pen stroke data, but also because it shows that this is a good approach in generally. Historically, machine learning researchers have tended to design a new, niche model architecture for every new data format. This allowed them to add inductive biases to their models and thus address idiosyncratic aspects of the task at hand. A good example might be of Graves (2014) using a mixture density network at the final layer of the RNN architecture to capture multimodal distributions over pen coordinates.

This work, along with works like Pointer Networks2, supports the idea that it is better to design a custom tokenizer than a custom model. If one can recast a niche data format or novel task as a token-based sequence modeling problem, one can immediately train a vanilla GPT model on it. Not only are GPT-style models scalable, well-studied, and easy to construct via open source libraries – they also come with a set of stable hyperparameters and training best practices.

Mapping continuous spaces to bins. One specific modeling dynamic we found interesting was the mapping of continuous Cartesian coordinate data to tokens. In many continuous modeling problems, researchers don’t do this: instead, they train directly on continuous variables with an RMSE loss. But that approach comes with some downsides. First of all, there is an implicit Gaussian distribution around each scalar output of an MLP.3 If the target variables are not Gaussian-distributed (for example, pen strokes which have a power-law distribution with respect to stroke distances), then models often struggle to capture the long tail of the distribution. Solutions like mixture density networks help address this issue, but come with their own set of challenges.4 By contrast, when one bins continuous data and tokenizes the bin indices, one is able to train with a cross entropy loss, which generally works much better than an RMSE loss, and capture skew and multimodal distributions with ease. Indeed, it is possible that most, if not all problems that use continuous variables can be modeled at least as well via with binning and tokenization.

Closing thoughts. Cursive handwriting is a unique, small-scale sequence modeling problem that can serve as a rich testbed for sequence modeling research. It is also a culturally-significant art form that people use to express emotions and personality. We believe that it is understudied in machine learning, and in this work we have sought to remedy that problem by introducing a new dataset and training a simple GPT-style model to generate realistic cursive handwriting. The results are among the best we have seen for pen-stroke models and are competitive with the best image-based methods. We believe that they also contain broader insights about how Transformers can be used for modeling niche data modalities.

Footnotes

-

Graves, Alex. “Generating sequences with recurrent neural networks.” arXiv preprint arXiv:1308.0850 (2013). ↩

-

Vinyals, Oriol, Meire Fortunato, and Navdeep Jaitly. “Pointer networks.” Advances in neural information processing systems 28 (2015). ↩

-

Bishop, Christopher M. Neural networks for pattern recognition. Oxford university press, 1995. ↩

-

Mixture density networks, for example, introduce a new hyperparameter and the multiplicative mixture coefficients, in general, make the MDN layer hard to train. ↩