Tocqueville excerpt from Democracy in America

Preliminary remarks by SJG

This page features an excerpt from Democracy in America by Alexis de Tocqueville, translated and edited by Harvey C. Mansfield and Delba Winthrop. It was written nearly two hundred years ago but many of its observations remain relevant to the culture and institutions of America in 2022. Although Tocqueville writes with an ostensibly neutral voice, we should note that he is very invested in the topics he discusses. From the book’s introduction,

“The entire book that you are going to read was written under the pressure of a sort of religious terror in the author’s soul, produced by the sight of this irresistible revolution that for so many centuries has marched over all obstacles, and that one sees still advancing today amid the ruins it has made…”

These are the words of a well-educated aristocrat mourning the loss of his class’ prominence and looking into the future with a mixture of awe and curiosity. With that in mind, let’s allow Tocqueville begin to speak for himself.

How, in the United States, religion knows how to make use of democratic institutions

I established in one of the preceding chapters that men cannot do without dogmatic beliefs and that it was even very much to be wished that they have them. I add here that among all dogmatic beliefs the most desirable seem to me to be dogmatic beliefs in the matter of religion; that may be deduced very clearly even if one wants to pay attention only to the interests of this world.

There is almost no human action, however particular one supposes it, that does not arise from a very general idea that men have conceived of God, of his relations with the human race, of the nature of their souls, and of their duties toward those like them. One cannot keep these ideas from being the common source from which all the rest flow.

Men therefore have an immense interest in making very fixed ideas for themselves about God, their souls, and their general duties toward their Creator and those like them; for doubt about these first points would deliver all their actions to chance and condemn them to a sort of disorder and impotence.

That, therefore, is the matter about which it is most important that each of us have fixed ideas; and unfortunately it is also the one in which it is most difficult for each person, left to himself, to come to fix his ideas solely by effort of his reason.

Only minds very free of the ordinary preoccupations of life, very penetrating, very agile, very practiced, can, with the aid of much time and care, break through to these so necessary truths.

Still we see that these philosophers themselves are almost always surrounded by uncertainties; that at each step the natural light that enlightens them is obscured and threatens to be extinguished, and that despite all their efforts, they still have been able to discover only a few contradictory notions, in the midst of which the human mind has constantly floated for thousands of years without being able to seize the truth firmly or even to find new errors. Such studies are much above the average capacity of men, and even if most men should be capable of engaging in them, it is evident that they would not have the leisure for it.

Some fixed ideas about God and human nature are indispensable to the daily practice of their lives, and that practice keeps them from being able to acquire them.

That appears to me to be unique. Among the sciences there are some that are useful to the crowd and are within its reach; others are accessible only to a few persons and are not cultivated by the majority, who need only their most remote applications; but the daily use of this [science] is indispensable to all, though its study is inaccessible to most.

General ideas relative to God and human nature are therefore, among all ideas, the ones it is most fitting to shield from the habitual action of individual reason and for which there is most to gain and least to lose in recognizing an authority.

The first object and one of the principal advantages of religions is to furnish a solution for each of these primordial questions that is clear, precise, intelligible to the crowd, and very lasting.

There are religions that are very false and very absurd; nevertheless one can say that every religion that remains within the circle I have just indicated and that does not claim to leave it, as several have attempted to do, in order to stop the free ascent of the human mind in all directions, imposes a salutary yoke on the intellect; and one must recognize that if it does not save men in the other world, it is at least very useful to their happiness and their greatness in this one.

That is above all true of men who live in free countries.

When religion is destroyed in a people, doubt takes hold of the highest portions of the intellect and half paralyzes all the others. Each becomes accustomed to having only confused and changing notions about matters that most interest those like him and himself; and one defends one’s opinions badly or abandons them, and as one despairs of being able to resolve by oneself the greatest problems that human destiny presents, one is reduced, like a coward, to not thinking about them at all.

Such a state cannot fail to ennervate souls; it slackens the springs of the will and prepares citizens for servitude.

Not only does it then happen that they allow their freedom to be taken away, but often they give it over.

When authority in the matter of religion no longer exists, nor in the matter of politics, men are soon frightened at the aspect of this limitless independence. This perpetual agitation of all things makes them restive and fatigues them. As everything is moving in the world of the intellect, they want at least that all be firm and stable in the material order; and as they are no longer able to recapture their former beliefs, they give themselves a master.

As for me, I doubt that man can ever support a complete religious independence and an entire political freedom at once; and I am brought to think that if he has no faith, he must serve, and if he is free, he must believe.

I do not know, however, whether this great utility of religions is not still more among peoples where conditions are equal than among all others.

One must recognize that equality, which introduces great goods into the world, nevertheless suggests to men very dangerous instincts, as will be shown hereafter; it tends to isolate them from one another and to bring each of them to be occupied with himself alone.

It opens their souls excessively to the love of material enjoyments.

The greatest advantage of religions is to inspire wholly contrary instincts. There is no religion that does not place man’s desires beyond and above earthly goods and that does not naturally raise his soul toward regions much superior to those of the senses. Nor is there any that does not impose on each some duties toward the human species or in common with it, and that does not thus draw him, from time to time, away from contemplation of himself. This one meets even in the most false and dangerous religions.

Religious peoples are therefore naturally strong in precisely the spot where democratic peoples are weak; this makes very visible how important it is that men keep to their religion when becoming equal.

I have neither the right nor the will to examine the supernatural means God uses to make a religious belief reach the heart of man. For the moment I view religions only from a purely human point of view; I seek the manner in which they can most easily preserve their empire in the democratic centuries that we are entering.

I have brought out how, in times of enlightenment and equality, the human mind consents to receive dogmatic beliefs only with difficulty and feels the need of them keenly only in the case of religion. This indicates first that in those centuries more than in all others religions ought to keep themselves discreetly within the bounds that are proper to them and not seek to leave them; for in wishing to extend their power further than religious matters, they risk no longer being believed in any matter. They ought therefore to trace carefully the sphere within which they claim to fix the human mind, and beyond that to leave it entirely free to be abandoned to itself.

Mohammed had not only religious doctrines descend from Heaven and placed in the Koran, but political maxims, civil and criminal laws, and scientific theories. The Gospels, in contrast, speak only of the general relations of men to God and among themselves. Outside of that they teach nothing and oblige nothing to be believed. That alone, among a thousand other reasons, is enough to show that the first of these two religions cannot dominate for long in enlightened and democratic times, whereas the second is destined to reign in these centuries as in all the others.

If I continue this same inquiry further, I find that for religions to be able, humanly speaking, to maintain themselves in democratic countries, they must not only confine themselves carefully to the sphere of religious matters; their power depends even more on the nature of the beliefs they profess, the external forms they adopt, and the obligations they impose.

What I said previously, that equality brings men to very general and vast ideas, ought to be understood principally in the matter of religion. Men who are alike and equal readily conceive the notion of a single God imposing the same rules on each of them and granting them future happiness at the same price. The idea of the unity of the human race constantly leads them back to the idea of the unity of the Creator, whereas on the contrary, men very separate from one another and very unalike willingly come to make as many divinities as there are peoples, castes, classes and families, and to trace a thousand particular paths for going to Heaven.

One cannot deny that Christianity itself has in some fashion come under the influence exerted over religious beliefs by the social and political state.

At the moment when the Christian religion appeared on earth, Providence, which was undoubtedly preparing the world for its coming, had united a great part of the human species, like an immense flock, under the scepter of the Caesars. The men who composed that multitude differed much from one another, but they nevertheless had this common point: they all obeyed the same laws; and each of them was so weak and small in relation to the greatness of the prince that they all appeared equal when one came to compare them to him.

One must recognize that this new and particular state of humanity ought to have disposed men to receive the general truths taught by Christianity, and serves to explain the easy and rapid manner with which it then penetrated the human mind.

The corresponding proof came after the destruction of the Empire.

As the Roman world was then shattering, so to speak, into a thousand shards, each nation returned to its former individuality. Inside those nations, ranks were soon graduated to infinity; races were marked out, castes partitioned each nation into several peoples. In the midst of this common effort that seemed to bring human societies to subdivide themselves into as many fragments as it was possible to conceive, Christianity did not lose sight of the principal general ideas it had brought to light. But it nonetheless appeared to lend itself, as much as it could, to the new tendencies arising from the fragmentation of the human species. Men continued to adore one God alone as creator and preserver of all things; but each people, each city, and so to speak each man, believed himself able to obtain some separate privilege and to create for himself particular protectors before the sovereign master. Unable to divide the Divinity, they at least multiplied it and magnified its agents beyond measure; the homage due to angels and saints became an almost idolatrous worship for most Christians, and one could fear a moment might come when the Christian religion would regress to the religions it had defeated.

It appears evident to me that the more the barriers that separate nations within humanity and citizens within the interior of each people tend to disappear, the more the human mind is directed, as if by itself, toward the idea of a single omnipotent being, dispensing the same laws to each man equally and in the same manner. It is therefore particularly in centuries of democracy that it is important not to allow the homage rendered to secondary agents to be confused with the worship that is due only the Creator.

Another truth appears very clear to me: that religions should be less burdened with external practices in democratic times than in all others.

I have brought out, concerning the philosophic method of the Americans, that nothing revolts the human mind more in times of equality than the idea of submitting to forms. Men who live in these times suffer [representational] figures with impatience; symbols appear to them to be puerile artifices that are used to veil or atorn for their eyes truths it would be more natural to show to them altogether naked and in broad daylight; the sight of ceremonies leaves them cold, and they are naturally brought to attach only a secondary importance to the details of worship.

Those charged with regulating the external form of religions in democratic centuries ought indeed to pay attention to these natural instincts of human intelligence in order not to struggle unnecessarily against them.

I believe firmly in the necessity of forms; I know that they fix the human mind in the contemplation of abstract truths, and by aiding it to grasp them forcefully, they make it embrace them ardently. I do not imagine that it is possible to maintain a religion without external practices; but on the other hand, I think that in the centuries we are entering, it would be particularly dangerous to multiply them beyond measure; that one must rather restrict them, and that one ought to retain only what is absolutely necessary for the perpetuation of the dogma itself, which is the substance of religions, whereas worship is only the form. A religion that would become more minute, inflexible, and burdened with small observances at the same time that men were becoming more equal would soon see itself reduced to a flock of impassioned zealots in the midst of an incredulous multitude.

I know that one will not fail to object that since all religions have general and eternal truths for their object, they cannot so yield to the inconstant instincts of each century without losing the character of certainty in the eyes of men: I shall still respond here that one must distinguish very carefully the principal opinions that constitute a belief and that form what theologians call articles of faith, from the accessory notions that are linked to them. Religions are obliged always to hold firm in the first, whatever the particular spirit of the times may be; but they would do well to keep from binding themselves in the same manner to the second in centuries in which everything constantly changes place and in which the mind, habituated to the moving spectacle of human things, suffers itself to be held fixed only with regret. Immobility in external and secondary things appears to me to have a chance of lasting only when civil society itself is immobile; everywhere else, I am brought to believe that it is a peril.

We shall see that among all the passions that equality gives birth to or favors, there is one that it renders particularly keen and that it sets in the hearts of all men at the same time: the love of well-being. The taste for well-being forms the salient and indelible feature of democratic ages.

One may believe that a religion that undertook to destroy this mother passion would in the end be destroyed by it; if it wanted to tear men entirely from contemplation of the goods of this world to deliver them solely to the thought of those of the other world, one can foresee that their souls would finally escape from its hands to go plunge themselves, far away from it, only in material and present enjoyments.

The principal business of religions is to purify, regulate, and restrain the too ardent and too exclusive taste for well-being that men in times of equality feel; but I believe that they would be wrong to try to subdue it entirely and to destroy it. They will not succeed in turning men away from love of wealth; but they can still persuade them to enrich themselves only by honest means.

This leads me to a final consideration that in some fashion comprises all the others. As men become more alike and equal, it is more important that religions, while carefully putting themselves out of the way of the daily movement of affairs, not collide unnecessarily with the generally accepted ideas and permanent interests that reign among the mass; for common opinion appears more and more as the first and most irresistible of powers; there is no support outside of it strong enough to permit long resistance to its blows. That is no less true in a democratic people subject to a despot than in a republic. In centuries of equality, kings often make one obey, but it is always the majority that makes one believe; it is therefore the majority that one must please in all that is not contrary to the faith.

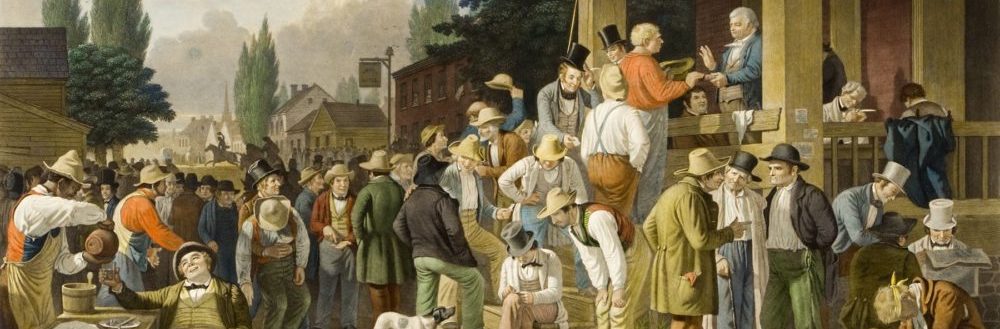

I showed in my first work how American priests keep their distance from public affairs. This is the most striking, but not the only, example of their restraint. In America religion is a world apart, where the priest reigns, but which he is careful never to leave; within its limits he guides intelligence; outside of it, he leaves men to themselves and abandons them to the independence and instability that are proper to their nature and to the times. I have not seen a country where Christianity wraps itself in less forms, practices, and [representational] figures than the United States, and presents ideas more clearly, simply, and generally to the human mind. Although Christians of America are divided into a multitude of sects, they all perceive their religion in the same light. This applies to Catholicism as well as to other beliefs. There are no Catholic priests who show less taste for small, individual observances, for extraordinary and particular methods of gaining salvation, or who cling more to the spirit of the law and less to its letter, than the Catholic priests of the United States; nowhere does one teach more clearly or follow better the doctrine of the Church that forbids rendering to saints the worship that is reserved only for God. Nevertheless, Catholics of America are very submissive and very sincere.

Another remark is applicable to the clergy of all communions: American priests do not try to attract and fix all the attentions of man on the future life; they willingly abandon a part of his heart to present cares; they seem to consider the goods of the world as important although secondary objects; if they do not associate themselves with industry, they are at least interested in its progress and applaud it, and while constantly showing to the faithful the other world as the great object of their hopes and fears, they do not forbid them from honestly searching for well-being in this one. Far from bringing out how these two things are divided and contrary, they rather apply themselves to finding the spot at which they touch and are bound to each other.