The Stepping Stones of Flight

By the year 1900, humans seemed to have figured out all the important ideas of aviation. There were patents for dozens of self-powered aircrafts including biplanes,1 seaplanes,2 and bombers.3 There were also designs for retractable landing gear,4 aileron wing controls,5 and curved airfoils.6 To many people, these designs indicated that the age of the airplane was at hand. Indeed, by this time there were already two commercial airline startups7 and one program for constructing bombers, fully funded by the French government.3 But there was just one problem: nobody had managed to fly a real airplane yet. In fact, the Wright brothers were still several years from achieving that breakthrough. As for bombers, seaplanes, and airline companies – such things were still many decades away.

This bizarre gap between theory and practice brings into question the meaning of the word invention. Generally speaking, one would think of an invention as a detailed design of the sort that could be patented. But in the case of the airplane, dozens of people patented airplanes that never could have flown. Did those people really invent airplanes? Otto Lilienthal, the first glider pilot, would have answered in the negative. “To design an aircraft is nothing” he wrote, “To build one is something. But to fly is everything.”

Airfoils

In order to focus on the practical stepping stones of flight, let’s adopt Lilienthal’s perspective. In other words, let’s focus on the changes in wing design that led to the most significant empirical improvements in flight. When we start down this path, one of the first things we notice is that most of these improvements are related to the cross-sectional shape of a wing, also known as the airfoil. Generally speaking, an airfoil has no moving parts. In fact, it is just a two-dimensional shape that influences the speed of air above and below a wing. Prior to the Wright brothers, few people gave serious thought to airfoil design. But it just so happened that the details of this shape play a critical role in determining the lift and drag profile of a wing. Only through repeated iteration of design and demonstration did we become aware of the airfoil’s surprising complexity.

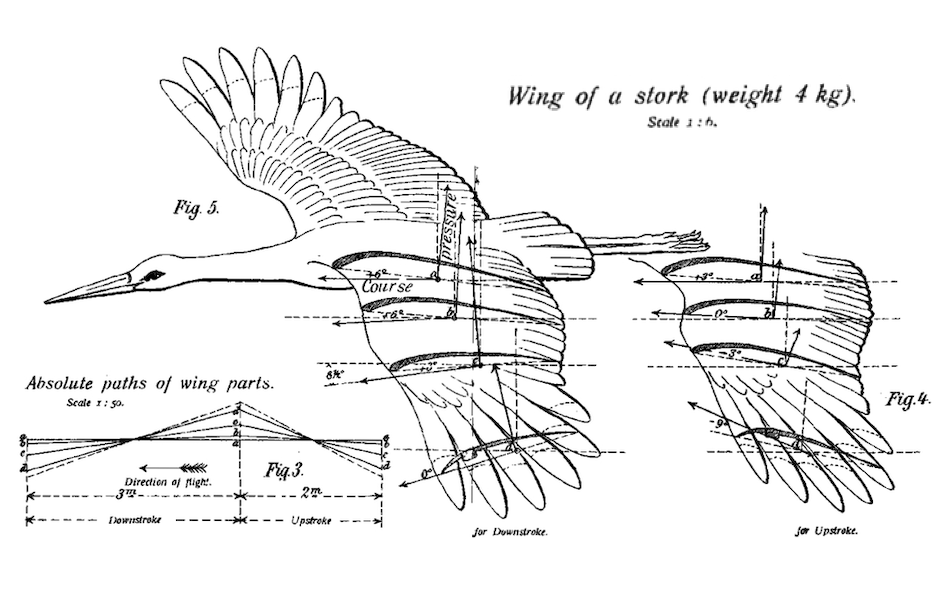

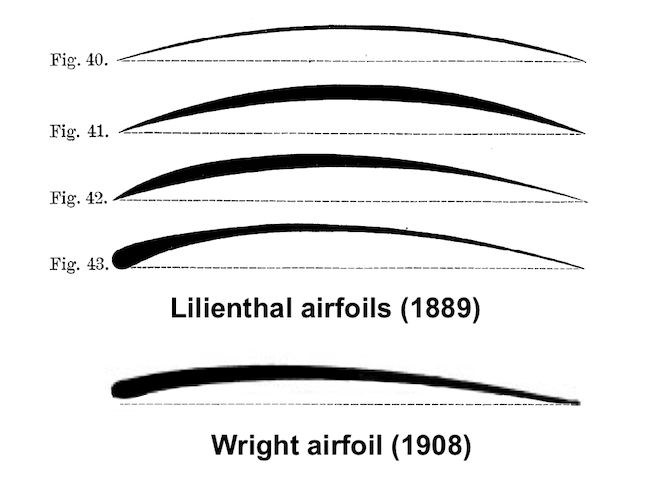

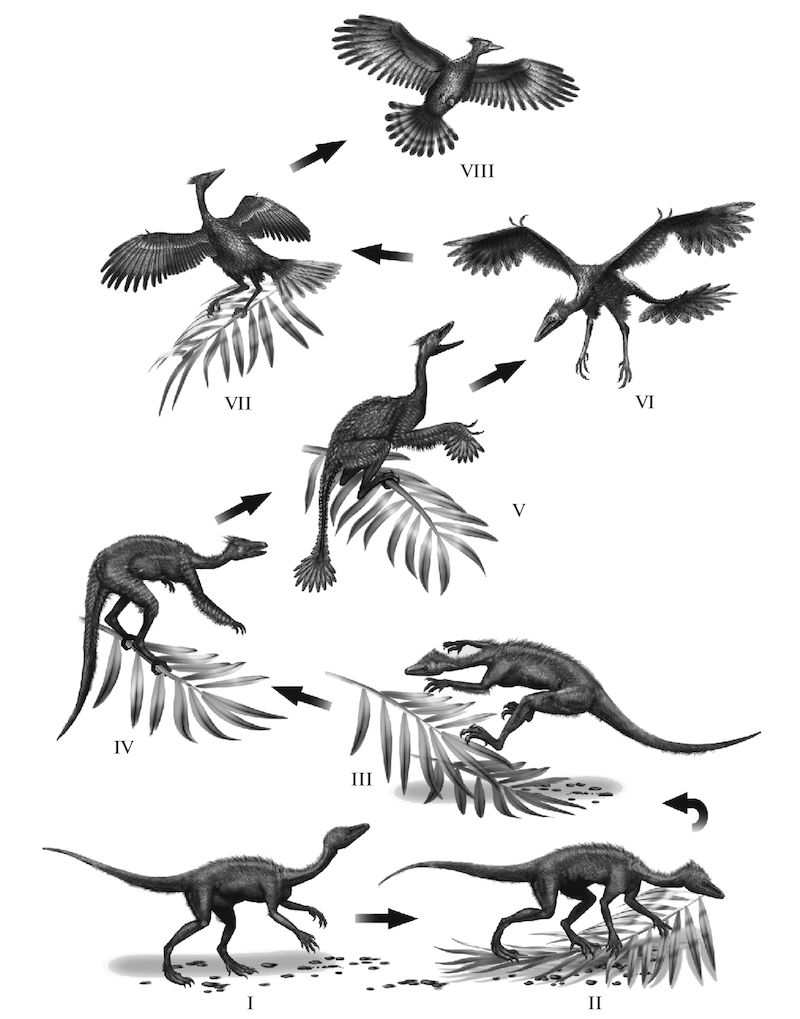

Lilienthal, with his emphasis on practical results, was the first person to realize how much airfoils matter. They came to his attention when he set out to build a glider that could support the weight of a man. In order to build such an apparatus, he needed to know how the lift and drag characteristics of various wings scaled with length, width, and thickness. In thinking about these questions, he quickly realized that the cross-sectional shape was an important design parameter. He started by studying the airfoils of bird wings, especially those of storks. Then, with their shapes in mind, he built artificial replicas in his laboratory and tested their lift coefficients. These methodical experiments took nearly twenty years of work, after which he published his findings in his thorough (and beautifully illustrated) book, Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation.8 Taking what he had learned from biology, Lilienthal spent the latter part of his life building and flying human-scale gliders – the first winged flying machines that could carry a human through the air. And so, with an eye on nature and great attention to detail, Lilienthal achieved the goal he had been working towards since his twenties.

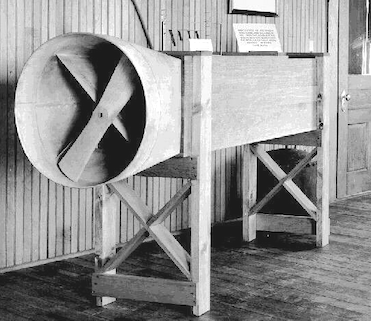

But even Lilienthal, for all his care, made some errors. The Wright brothers used his results to design their first glider, and when that glider crashed unexpectedly, they realized that something was wrong. After performing their own set of wind tunnel experiments, they determined that the widely-accepted value of the Smeaton coefficient – a key part of Lilienthal’s lift and drag equations – was about 60% too high.9 Starting from this discovery, they reworked their entire wing design. They tested out hundreds of airfoils in a miniature wind tunnel and finally settled on a new airfoil shape. It was slightly wider and more arched, and the highest point of its arch was closer to the front of the wing (more “forward camber”). In spite of these changes, it looked only slightly different from their original wing shape. And yet its improved lift and stability was what the Wrights needed in order to build the world’s first self-propelled airplane.

Although Lilienthal and the Wrights lived on different continents and had very different lives, they were united by the fact that they each spent years doing tedious, small-scale experiments in order to understand flight on a deep level. Only after this exploratory phase did they build real flying machines. In a way, those long hours of tedium are a sacrifice one must make when they set out to pursue the romantic ideal of flight. In profiling the early aviators, we saw that the frontier of flight often attracted radical and temperamental dreamers. These were not reliable people. And yet each of them had to discipline and civilize themselves, becoming the most practical of the lot of us, before they could become heroes. Interestingly, the next breakthroughs in flight were to involve the same dynamic, but this time playing out across nations rather than individuals. This was the era of the national labs.

The National Labs

National labs were a new phenomenon that emerged in the 1910’s and 1920’s as forward-thinking governments started to reckon with the military and economic applications of flight. Leading up to World War I, airplanes were still slow, unreliable, and expensive. They were great for stunts and parades, but close to useless on the battlefield. One of the main goals of the national labs was to change this.

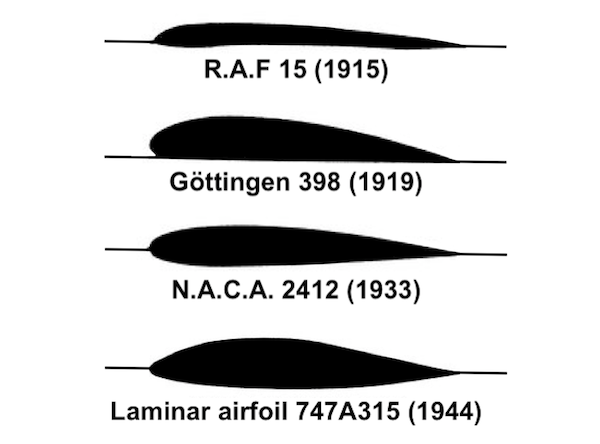

The first improvements in airfoil design came out of Britain’s National Physical Laboratory. Managers at this lab used its infrastructure and manpower to test airfoil designs much more thoroughly than the hobbyist-inventors before them. One of their key findings was that thicker wings with even more forward camber gave better lift. As soon as they made this discovery, they built it into military planes like the Airco DH.2 fighter (1915) and the Vickers Vimy bomber (1917).

But even though these changes in airfoil design improved lift, they did not improve stability. World War I era biplanes suffered from a dangerous effect called “thin airfoil stall.” This effect occurred when streams of air above and below a wing collided behind it, creating unpredictable drag and sending the plane into a stall. German engineers were the first to find a solution to this problem. They found that thicker airfoils like the Göttingen 398 could mitigate thin airfoil stall and make fighter planes more maneuverable. They used these insights to build the Fokker Dr. I (1917) which was one of the most dangerous fighters of the war.10

The most amazing thing about flight research during World War I was the speed at which national labs turned research into real technology. Often it only took a year or two. The condensed timeline and extreme real-world impact of airplanes led to dramatic improvements in their designs and finalized their transition from the world of ideas to the world of things. And the wonderful thing about having an idea take root in the world is its tendency to become the bedrock for an entirely new generation of ideas.

That is the story of the 1920’s and 1930’s, which is when the mathematical theory of flight got started. Government physicists in the United States finally had time to come up with theories that explained experimental results. Then they used these theories to make airfoils better in small but important ways. Their work culminated in the 1933 National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) Report 460, which set the industry standard for the next several decades. World War II planes like the DC-2 transport and the B-17 Flying Fortress used these results.11 And after the war, designs like the NACA 2412 found their way into commercial plane designs, some of which are still in use today.

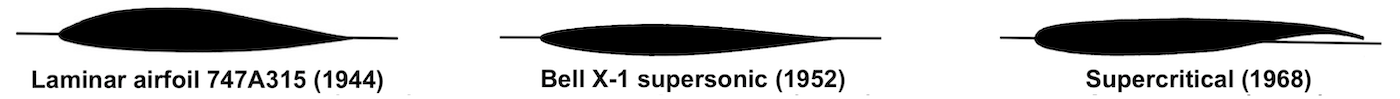

The process of minor improvements based on theory continued into the 1940’s, when NACA researchers invented the laminar flow airfoil and installed it on the P-51 Mustang.11 In practice, the laminar flow “correction” was rather small and it led to modest improvements. But it represented a milestone in that it was one of the first major innovations motivated by theory rather than human intuition or observations of biology. Focusing on the causal mechanisms of flight ended up being crucial for later innovations in the supersonic regime since the way air behaves at those speeds is much less intuitive.

In fact, there is a deep connection between how well we understand the laws of nature and what we can build in the world. The laws of nature are the rules of the game. We are constantly learning more about these rules and we can only innovate in proportion to how well we understand them. To see this, consider evolution for a moment. Over millions of years, it has deformed life so as to probe the laws of nature at many different scales. So with time, the fundamental forces of nature have constrained and shaped life into the variety of forms we see today. Human design mimics this trial-and-error approach, but our mental models of the world give us an advantage. They speed our search in proportion to how much of the physical world they can explain. And by acting on our mental models, we can make intuitive leaps that evolution, in all of its billions of years, never could have managed. One such intuitive leap was made by Richard Whitcomb when he discovered supercritical airfoils.

Supercritical Airfoils

This discovery occurred in 1965, which was a time when the aerospace industry was trying to improve supersonic flight. Jet engines, which were invented at the end of World War II, had improved to the point where they produced enough force to accelerate planes to supersonic speeds. But once planes reached these speeds, the physics of airflow started to change and existing airfoil designs stopped working. NACA researchers realized that they would have to rethink every aspect of wing design in order to adapt. One of the most challenging problems was what to do with airfoil design.11

At the time, many of Whitcomb’s colleagues were looking for solutions in aerodynamic theory. Whitcomb took a different approach: he grabbed a can of putty and headed for the Langley wind tunnel.12 He knew that the problem with existing airfoils was that air flowed at a higher rate around the top of the wing than the bottom. As the plane approached supersonic speeds, the air on top was the first to hit the sound barrier. Energy, normally dissipated as sound, would then be moving at the same speed as the air itself and slowly start to accumulate. A shock wave would form. Then the shock wave would create all sorts of pathological drag and instabilities.13

With this in mind, Whitcomb used putty to decrease the camber of the wing so as to lower the airspeed above it. Then he added a slight concavity to the underside of the wing to maintain lift and stability. All of this was based on his intuition for how air flowed over a wing at high speeds, but it ended up being extraordinarily effective. His “supercritical” wing design allowed the United States to build the fastest bombers, fighters, and reconnaissance planes of the Cold War. And surprisingly, this wing design turned out to be stable and efficient even at subsonic speeds. Today’s commercial airliners, which cruise at speeds around Mach 0.85, all use supercritical airfoils to improve fuel efficiency.

Looking over the history of wing design, it is easy to see that the boundary between imagination and the constraints of the real world is where invention happens. When ideas are fully constrained to our minds, we have the tendency to indulge in impractical fantasies. And yet we need imagination too. For without it, we are limited to the incremental trial-and-error pace of evolution. Imagination is our one clear advantage over evolution, for it requires no intermediary. For evolution to invent a wing, there needed to be a half-winged precursor. But imagination has a strangely liberating effect in that it allows us to move from the ground to the sky in a single intuitive leap.

Physical Theories

Since the first half of the twentieth century when the core breakthroughs of aeronautics occurred, scientists have been hard at work on physical theories that can explain those breakthroughs. These theories have expanded into fields of study like “computational fluid dynamics,” “aeronautical science,” and “turbulent flow.” Such principles are quite complex, but the question they aim to answer is simple: how do wings work? We are going to answer that question in the next section by obtaining our own wing starting from nothing but the physics of airflow.

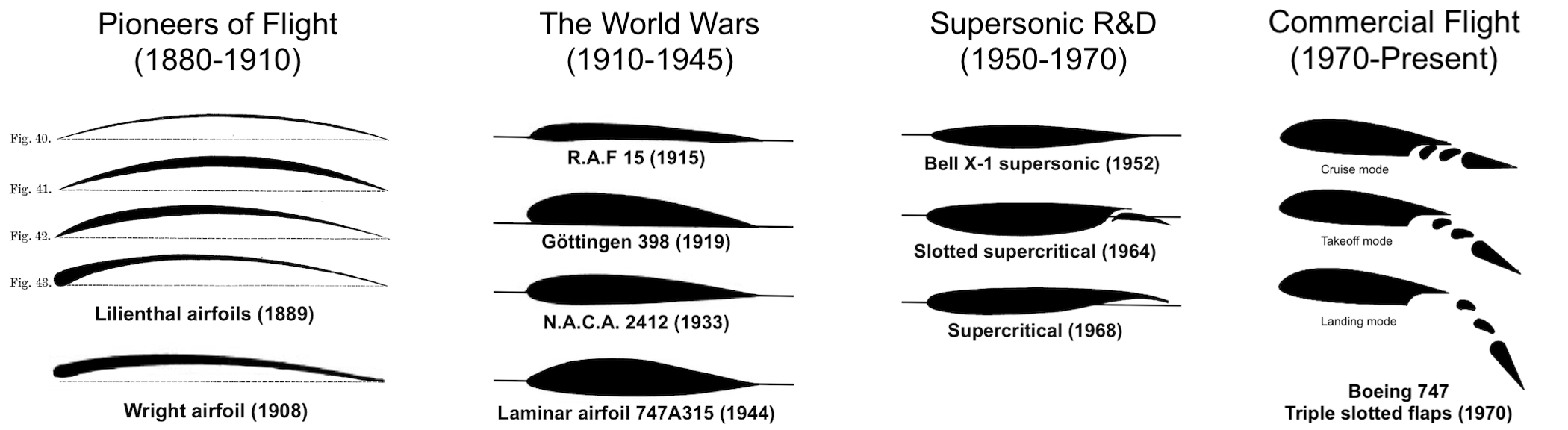

Appendix: Airfoil Timeline

Here is a complete timeline of the airfoils we discussed in this post. Outlines in the first three columns were obtained from primary sources and are technically accurate. Outlines in the fourth row are believed to be technically accurate – or close 🤷♂️

Footnotes

-

Wenham, Francis Herbert. On aërial locomotion and the laws by which heavy bodies impelled through the air are sustained, Annual Report of the Aëronautical Society of Great Britain, p. 10-20, 1866. ↩

-

Allward, Maurice. An Illustrated History of Seaplanes and Flying Boats, New York: Dorset Press, p. 11, 1981. ↩

-

Crosby, Francis. The Complete Guide to Fighters & Bombers of the World: An Illustrated History of the World’s Greatest Military Aircraft, London: Anness Publishing Ltd., p. 16, 2006. ↩ ↩2

-

Gibbs-Smith, Charles Harvard. Aviation. London: NMSI, p. 57, 2003. ↩

-

Boulton, Matthew Piers Watt. On Aerial Locomotion. Bradbury & Evans, London, 1864. ↩

-

Gibbs-Smith, 2003. p. 68. ↩

-

National Air and Space Museum. The Ariel: The First Carriage Of The Ærial Transit Company. National Air and Space Museum Collection, 1843. ↩

-

Otto Lilienthal. Birdflight as the Basis of Aviation. Longmans, Green, and Co., London, 1 edition, 1889. ↩

-

The wrong value of this coefficient had been in use for more than a hundred years and was part of the accepted equation for lift. So in determining that this number was wrong, the Wrights made a major discovery. ↩

-

Topnotch Gist. The History And Evolution of Modern Airplane Wing Design. YouTube, 2020. ↩

-

Airfoils and Supercritical Airfoils. Century of Flight. ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Garrison, Peter. The Man Who Could See Air. Air & Space Magazine, 2002 ↩

-

Many of the airfoil shapes used in this post were taken from NASA’s historical archives. See “SP-4305 Engineer in Charge” NASA History Division, 1986. ↩